Understanding the Relationship Between Heating Systems and Moisture

Why condensation happens, what heating really does, and how to stay dry in cold-weather camper vans

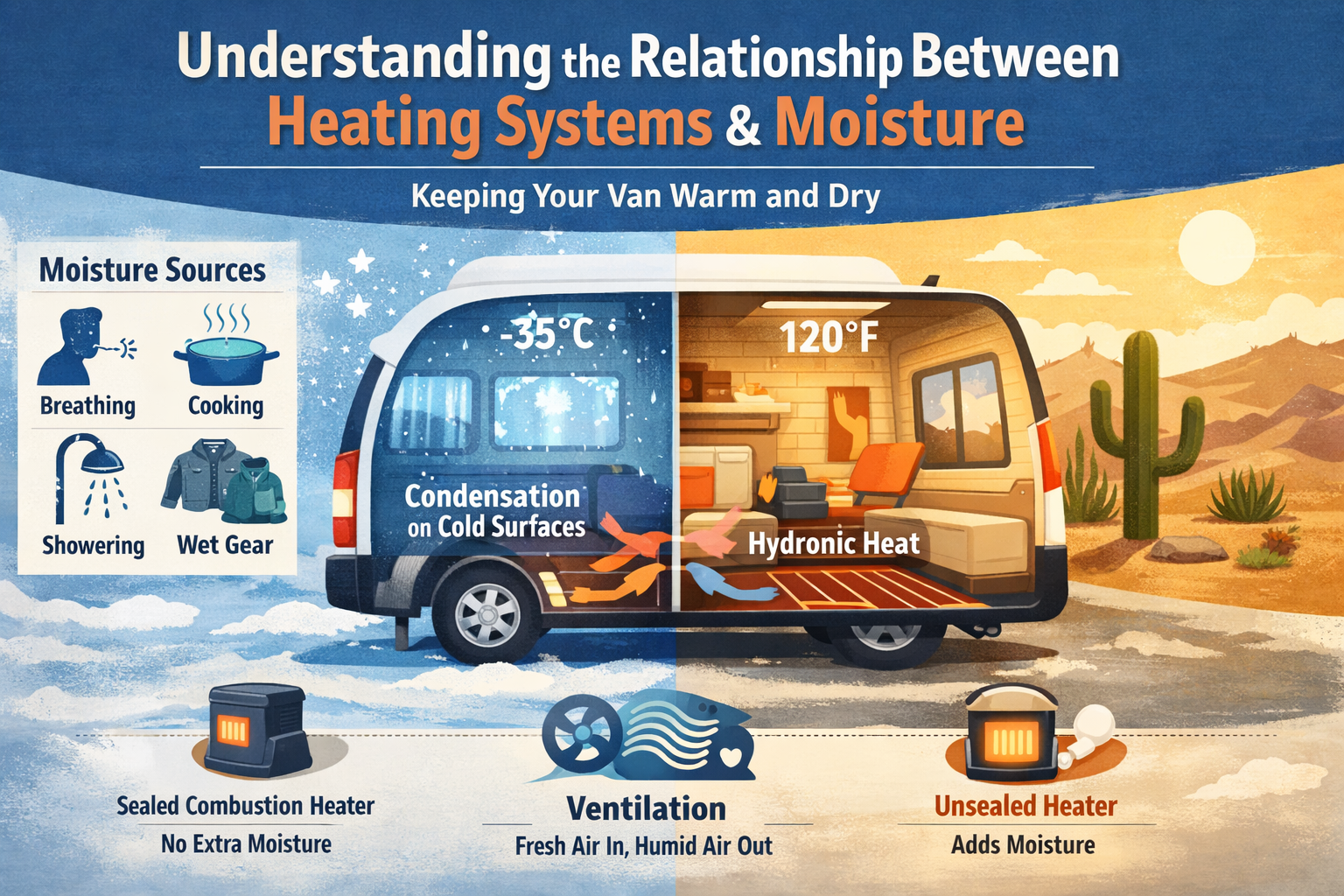

Moisture and condensation are among the most common—and most misunderstood—problems in camper vans, especially in cold climates. It’s easy to assume that choosing the “right” heating system will solve moisture issues, but the truth is more nuanced.

Heating systems influence comfort and surface temperatures, but they do not directly remove moisture. Understanding how heat, humidity, and ventilation interact is key to building a van that stays dry, healthy, and damage-free—whether you’re camping at -35°C on the prairies or dealing with cold desert nights after a hot day.

Where moisture in a camper van actually comes from

Before looking at heating systems, it’s important to understand the sources of moisture inside a van. Even a perfectly sealed build generates water vapor simply by being occupied.

Common moisture sources include:

- Breathing: Each adult exhales roughly 0.5–1.0 litres of water per day

- Cooking (especially boiling water)

- Showering

- Wet gear: snow-covered boots, jackets, pets

- Ambient humidity carried in with outside air

This moisture is always present. The question is not whether it exists, but where it ends up.

Why condensation forms

Condensation occurs when warm, moist air contacts a surface whose temperature is below the air’s dew point. When this happens, water vapor turns into liquid water—or frost in very cold conditions.

In camper vans, condensation most often appears on:

- Windows and windshields

- Metal ribs and structural framing

- Exterior-adjacent cabinetry

- Floors near doors and wheel wells

In extreme cold, condensation can freeze instantly, hiding moisture problems until temperatures rise and water appears inside walls or under floors.

What heating systems actually do (and don’t do)

A critical misconception is that some heating systems “dry” the air while others do not.

Heating does not create moisture, and it does not remove moisture. Heating simply raises air temperature, which allows air to hold more water vapor. If that moisture is not removed through ventilation, humidity will continue to rise—regardless of the heating method.

What heating does influence is:

- Air temperature

- Surface temperature

- Air movement

These factors affect where condensation forms and how visible it becomes.

Forced-air heating and moisture

Forced-air heaters (gasoline, diesel, or propane sealed-combustion systems) heat the cabin by blowing warm air through ducting.

How forced-air heat influences condensation:

- Air circulation: Moving air reduces cold pockets where condensation forms.

- Rapid surface warming: Blown air can quickly raise wall and window temperatures above the dew point.

This often leads to the perception that forced-air heat is “drier.” In reality:

- Forced-air systems do not remove moisture.

- They can delay visible condensation while humidity continues to rise.

Key takeaway: Forced-air heating can help manage where condensation appears, but without ventilation it does not prevent moisture buildup.

Hydronic (radiant) heating and moisture

Hydronic systems heat surfaces—such as floors, radiators, or fan coils—using a heated fluid loop. These systems are often described as producing “drier” heat.

From a physics standpoint, hydronic heat is not drier.

What hydronic systems do well:

- Create more even temperature distribution

- Reduce cold-soak in floors and lower walls

- Minimize sharp temperature swings

This can reduce condensation indirectly by keeping surfaces warmer and above the dew point—particularly floors and plumbing areas.

However:

- Hydronic systems do not ventilate the van

- They do not remove humidity from the air

- Moisture will still accumulate without fresh-air exchange

The comfort people associate with hydronic heat comes from warm surfaces, not lower humidity.

Combustion type matters more than heat distribution

The most important moisture distinction is not forced-air versus hydronic—it is sealed versus unsealed combustion.

- Sealed-combustion heaters draw combustion air from outside and exhaust all combustion byproducts—including water vapor—outside the van.

- Unsealed heaters (open propane or catalytic heaters) release water vapor directly into the living space.

Unsealed combustion heaters dramatically increase interior humidity and are a leading cause of winter condensation, frost buildup, and mold.

For cold-climate camper vans, sealed combustion is essential.

The real solution: ventilation

Condensation control is fundamentally a ventilation problem, not a heating problem.

Effective moisture management requires:

- Controlled fresh-air intake

- Consistent airflow—even in extreme cold

- Targeted exhaust during cooking and showering

Counterintuitively, bringing in cold outside air often helps. Cold air holds very little moisture; once heated, it can absorb interior humidity and carry it out of the van.

How heating and ventilation work together

The healthiest vans use heating and ventilation as a system:

- Forced-air + ventilation: Quickly warms surfaces and dries visible condensation.

- Hydronic + ventilation: Keeps floors and hidden spaces warm, reducing long-term moisture risk.

- Any heater without ventilation: Leads to moisture buildup over time.

Key takeaways

- Heating systems do not remove moisture—ventilation does.

- Forced-air heat manages air movement; hydronic heat manages surface temperatures.

- No heating system is inherently “dry.”

- Sealed-combustion heaters are critical in cold climates.

- Consistent, intentional ventilation is the single most important factor in preventing condensation.

Understanding this relationship allows builders and travelers to make informed decisions—creating vans that are not only warm, but dry, durable, and comfortable through real winter conditions.

Sign up with your email and always get notifed of Avada Lifestyles latest news!